Gov. Eric Greitens' decision last week to form a board of inquiry in the Marcellus Williams murder case was a step into uncharted territory.

It appears the state has formed few similar boards in the 54 years since state law first allowed it.

Gov. Mel Carnahan created two of them.

"It's a thoughtful way to deal with complex death penalty and other matters," Brad Ketcher, a St. Louis County lawyer who once served as Carnahan's legal counsel, said.

Boards of inquiry provide an "independent way" to review complex cases without the time pressures that come with last-minute appeals through state and federal courts, he added.

Joe Bednar agreed.

Bednar - a former Jackson County assistant prosecutor who now is a Jefferson City lawyer and who also served as Carnahan's chief counsel - said a board of inquiry "is a unique process" that deals with "difficult and hard issues" a governor is trying to balance with justice.

He explained, "That's your most important purpose of the process - to make sure that justice is served."

Greitens' order came Tuesday afternoon, less than five hours before Williams was scheduled to die by lethal injection for the August 1998 murder of Felicia "Lisha" Gayle in her home in University City.

Court records show Gayle was stabbed 43 times with a butcher knife from her own kitchen, with seven of the wounds determined as fatal blows.

A St. Louis County jury convicted Williams in 2001. A unanimous Missouri Supreme Court upheld the conviction and death sentence in January 2003.

St. Louis County Prosecutor Bob McCullough's office tried the original case, and the attorney general's office has handled the appeals.

Both said they're confident Greitens' board of inquiry will uphold what already has been decided.

"We remain confident in the judgment of the jury and the many courts that have carefully reviewed Mr. Williams' case over 16 years," said Loree Anne Paradise, Attorney General Josh Hawley's spokeswoman. "We applaud the work of the numerous law enforcement officers who have dedicated their time and effort to pursuing justice in this case."

But the Midwest Innocence Project reminded Greitens in a nine-page petition asking the governor to appoint an independent board of inquiry there is "no forensic evidence or eye-witness testimony tying Mr. Williams to the crime. Instead, the case is made up of circumstantial evidence and informant testimony."

The immediate, prominent issue for the governor and his staff was a recent DNA test done on the butcher knife - testing which had not been done after the original crime.

The Innocence Project told Greitens, "DNA testing of the murder weapon affirmatively excluded Mr. Williams as the perpetrator."

But the news release announcing the governor's decision to halt last week's execution said only: "DNA testing of the murder weapon, conducted in 2016, was inconclusive."

McCullough has said there's plenty of evidence tying Williams to the murder, including his selling a laptop stolen from Gayle's home.

Those are issues the board of inquiry now can examine.

Missouri's Constitution gives the governor "power to grant reprieves, commutations and pardons, after conviction, for all offenses except treason and cases of impeachment."

A 1963 state law gives the governor the authority to, "in his discretion, appoint a board of inquiry whose duty it shall be to gather information, whether or not admissible in a court of law, bearing upon whether or not a person condemned to death should be executed or reprieved or pardoned, or whether the person's sentence should be commuted."

Greitens said in a Tuesday news release: "A sentence of death is the ultimate, permanent punishment. To carry out the death penalty, the people of Missouri must have confidence in the judgment of guilt."

He said he was appointing the board "in light of new information" in the Williams case.

In his executive order, Greitens said the board "shall consider all evidence presented to the jury, in addition to newly discovered DNA evidence and any other relevant evidence not available to the jury."

He also said the board "shall have subpoena power over persons and things."

State law does not define the board's size, who should be its members or how long it may take to study the issues.

Greitens said he would name a five-member board that would "include retired Missouri judges" - but gave no other details.

The Innocence Project's petition noted Carnahan appointed a similar board in the mid-1990s to look at the Lloyd Schlup case, involving a death sentence for a young prison inmate accused of helping murder another inmate.

Tricia J. Bushnell, the Kansas City-based Midwest Innocence Project's director, and Barry Scheck, a co-founder of the national organization, wrote: "(Carnahan) personally made one selection (to the board) and asked counsel for Mr. Schlup and counsel for the (state) each to nominate two Missouri Circuit Judges to serve the Board."

Bednar also helped form a board in the William T. Boliek case, which also included retired judges.

He explained, "I think the retired judges took their jobs very seriously and were very thoughtful in their approach."

Bednar took part in the board of inquiry work and called it "one of the more interesting aspects of my job. There's always room for mistakes to be made and a time for additional information to be found out."

But Bednar said he never can comment on the board's work in the Boliek case, and the public never will know details of the Greitens board's work, either.

"That's all confidential by state law," he said. "(The governor) could give an explanation of what he decides to do. He always can announce the basis for his decision and offer facts or law that he thinks are relevant - because he also is not bound by the board of inquiry. They're just advisers."

In the Schlup case, the board didn't finish its work because the U.S. Supreme Court ordered a new trial.

Bednar said the board of inquiry process should be used sparingly.

"It really is for those unique or unusual circumstances," he said.

The law allows the board to subpoena witnesses and take testimony and evidence under oath - even if it's evidence that would not be admissible in a court.

"It gives the process and the governor the ability to have as much information as possible before he makes a decision," Bednar said.

And that's not any kind of "slap in the face" to the legal system or the jury process.

"I think it's all part of the process," Bednar explained, "and I think it's dangerous for people to select a portion of the process - and say that another portion is disrespectful. Those are all checks and balances that have been put in place (that) in the end is designed and hoped that you get the right result and justice is done."

Inmates are not entitled to have a board of inquiry.

Death row inmates Gary Roll and George B. Harris - who had been convicted for separate, unrelated murders - sued Carnahan and other state officials in 2000, asking the St. Louis-based U.S. District Court for Eastern Missouri to block their pending executions.

The trial court dismissed the case, deciding it was "frivolous" and failed "to state a claim on which relief may be granted."

The 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals heard arguments Aug. 28 and ruled a day later the district court was correct.

"Roll wants a board of inquiry to present evidence on his behalf," the brief 8th Circuit ruling said. "Appointment of a board of inquiry is also left to the governor's sole discretion, however, so Roll has no due process right to the appointment."

Roll was executed Aug. 30, and Harris was executed Sept. 13, 2000.

THE CARNAHAN CASES

Lloyd Schlup

Lloyd Schlup was 23 and already serving a life prison sentence for attempted murder when he was one of three white men accused in the Feb. 3, 1984, stabbing death of Arthur Dade, a black inmate at the Missouri State Penitentiary.

He was scheduled to die just after midnight Nov. 19, 1993.

Schlup argued his first lawyer - a private practice civil attorney who had been appointed to represent Schlup in the criminal case - neglected to present testimony that would have proved he was not one of three white men who ambushed Dade.

A federal appeals court judge later called the lawyer's performance "absolutely ineffective."

But two days before the scheduled execution, the St. Louis-based 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals rejected Schlup's appeal for a hearing of the new evidence.

So, just nine hours before the execution, then-Gov. Mel Carnahan issued a stay and ordered a board of inquiry.

The U.S. Supreme Court later ordered a new trial, so the board of inquiry's work was ended.

When the new trial was about to begin in Pulaski County on March 23, 1999, Schlup - who long had argued he wasn't even near the scene of Dade's murder - accepted a plea agreement allowing him to plead guilty to second-degree murder in exchange for a life prison sentence.

Then-Cole County Prosecutor Richard Callahan told the News Tribune Schlup's plea agreement included "the maximum sentence available" for a second-degree murder conviction.

His second sentence was to begin after he finished serving his first life sentence.

Callahan had been the assistant prosecutor who tried Schlup's original case before a St. Charles County jury, and said in 1999 he agreed to the plea deal partly because the case was 15 years-old by then, and "the chances of getting a conviction are substantially less. (But) from society's standpoint, an acknowledgment of participating in the crime also was important."

Missouri's Corrections Department said Schlup currently is serving his sentences at the Southeast Correctional Center in Charleston.

Case information is from news stories and court cases.

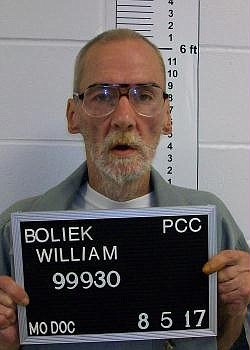

William T. Boliek

After William T. Boliek and a group of others robbed the home of an acquaintance in Kansas City in August 1993, Boliek and Vernon Wait began to discuss "getting rid of witnesses" to the robbery.

Boliek convinced his friends to drive to Thayer to hide out with his parents from the Kansas City authorities - and they robbed a liquor store in Nevada on the way.

While making a rest stop along Route M in Oregon County, Boliek killed Jody Harless - his lover's sister - and was sentenced to die after a trial in Camden County.

"It had gone through state appeals and been rejected," Jefferson City lawyer Joe Bednar, who served as then-Gov. Mel Carnahan's chief counsel, told the News Tribune last week. "It went through federal appeals, and U.S. District Judge Scott Wright had granted Boliek a new trial."

But the state appealed, and the 8th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals overturned Wright on "a procedural, not a substantive, reason."

Boliek asked the governor for clemency and, less than nine hours before the scheduled Aug. 26, 1997, execution, Carnahan ordered a stay and created a board of inquiry to review the case.

In his Aug. 25, 1997, executive order, Carnahan wrote the stay was effective "until such time as I make a final determination as to whether or not Boliek should be granted clemency."

But Carnahan had not made that decision before he was killed in an Oct. 16, 2000, plane crash while flying from St. Louis to the Missouri Bootheel.

Boliek remains on death row at the state prison in Potosi, essentially serving a life sentence without parole because no other governor can change Carnahan's language.

"It's a unique situation - a 'permanent' stay. The attorney general's office sought to execute (Boliek) in the Holden administration," Bednar said.

But the Missouri Supreme Court ruled Carnahan's use of the personal pronoun meant only he could make the final decision - leaving the stay of execution in place after Carnahan's death.

Case information is from Missourinet's "Missouri Death Row" website, missourideathrow.com/2008/12/Boliek-William, and from news stories. The Learfield Communications site bases its information on court records.