CHICAGO (AP) - Taking hormone pills for several years after menopause didn't shorten older women's lifespans, according to the longest follow-up yet of landmark research that transformed thinking on risks and benefits of a once popular treatment.

That research was halted early when unexpected harms were found from using replacement hormones - estrogen alone or with progestin - versus dummy pills for five to seven years. More breast cancer, heart attacks and strokes occurred in women on combined pills, and those on estrogen pills had more strokes.

But about 18 years of follow-up show that despite those risks, women had similar rates of deaths from heart disease, breast cancer and all other causes as those who took dummy pills.

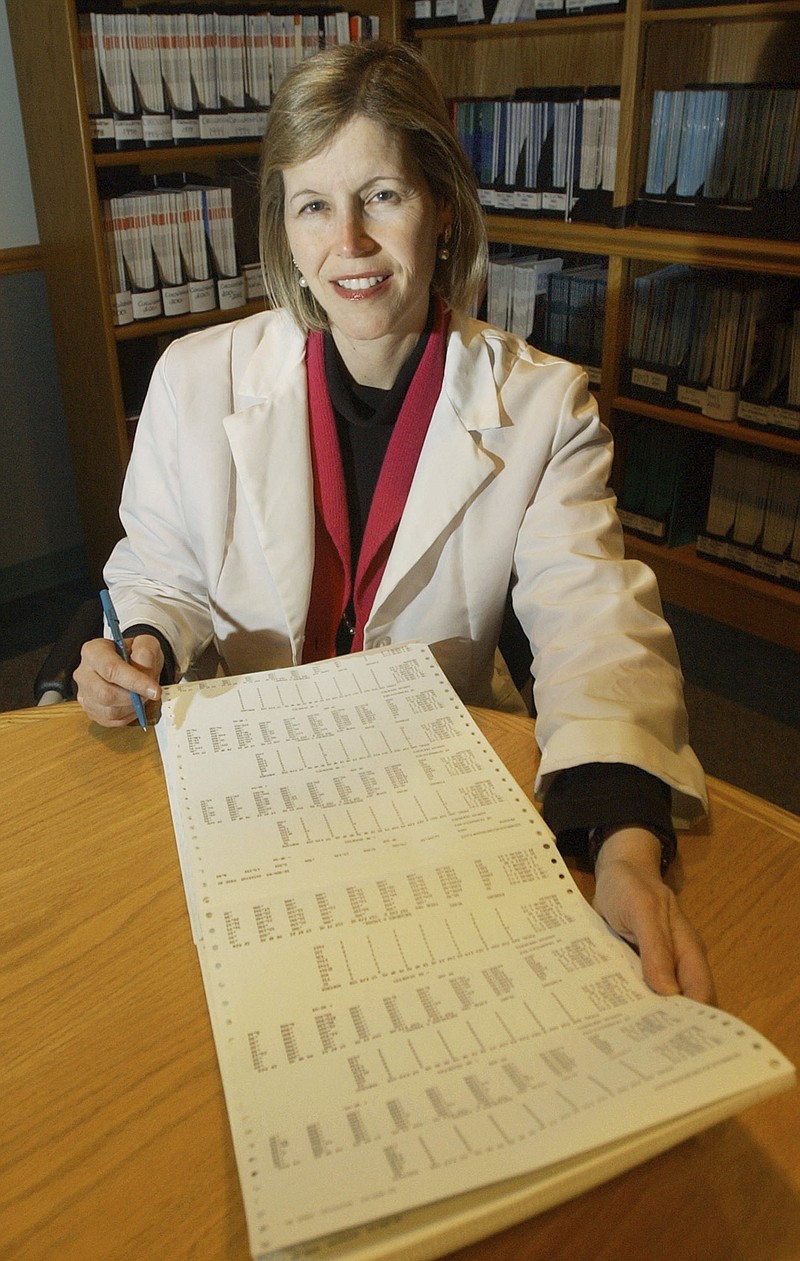

The new results are reassuring and support current advice: Hormones may be appropriate for some women when used short-term to relieve hot flashes and other bothersome menopause symptoms, said Dr. JoAnn Manson, preventive medicine chief at Boston's Brigham and Women's Hospital and lead author of the follow-up report.

"It's the ultimate bottom line," said Manson, who was also part of the original research. Women want to know "is this medication going to kill me" and the answer appears to be no, she said.

Results were published Tuesday in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

Hormones were once considered a fountain of youth for women entering menopause because of weak evidence suggesting a host of purported benefits including reducing heart disease and boosting memory. The landmark research, backed by the U.S. government, began in the early 1990s to rigorously test hormones' effects in older women randomly assigned to take the pills or dummy treatment. Brands studied were Prempro estrogen-progestin pills and Premarin estrogen-only pills.

The results led to advice against taking hormones to prevent age-related diseases. When used for menopause symptoms, the lowest possible dose for the shortest possible time was recommended, then as now. For some women already facing health risks, hormones' potential harms may outweigh any benefits, and discussions with a doctor about starting the treatment are advised.

Participants were aged 50 to 79 and past menopause, older than typical users, and took larger doses than currently recommended.

The follow-up involved most of the more than 27,000 women who were part of the original research. It included time using pills and about 10 or so years after stopping. Some earlier follow-ups suggested no increased risk of death in hormone users, but Manson said this is the first to focus only on deaths from various causes.

Overall, almost 7,500 women died - about 27 percent each in the hormone and dummy pill groups. Most deaths occurred after women stopped taking hormones. About 9 percent of women in both groups died from heart disease and about 8 percent from breast and other cancers.

Among the youngest women, there were fewer overall deaths early on among hormone users than dummy-pill users, but the rates evened out after women stopped using the pills.

Overall, death rates were similar among women on both types of hormone treatment versus dummy pills.

Prempro and Premarin are both approved to treat menopause symptoms and to prevent bone-thinning osteoporosis. Even so, many women and their doctors remain wary of hormone use. An editorial published with the follow-up study says the results "will hopefully alleviate concerns" about the long-term consequences.

More research is needed on risks and benefits of other types of hormones including patches, Manson said.