It's no wonder some early Missouri settlers feared caves were Satan's passages. In the firelight of their torches, the caves' otherworldly chandeliers, drapery and other calcite formations - awe inspiring as any artwork - seemed home to the supernatural. The state's caves are stuff of legend and literature, but there's more than myth housed in their chambers.

Missouri's limestone rich land is abundant with caves, more than any state besides Tennessee. For centuries, people have harbored in the rocky rifts for shelter, exploration and celebration. They have served as burial grounds and wedding chapels, mushroom farms and moonshine hideouts. But, the history of these caves far exceeds their human uses. These subterranean labyrinths are chronicles of natural development. Some are scientific troves that hold the remains of extinct animals dating back millennia.

The struggle for those invested in the caving system is allowing people to experience the majesty of these underground vaults while protecting the living and historical treasures they hold. Opening caves to the public makes it easier to promote research, but the more exposed a cave is, the more vulnerable. The risks are worth the reward as scientists look to private citizens to help fund future cave research.

Many of Missouri's caves were only recently reopened after white-nose syndrome decimated the bat population, and work is still being done to help them survive. White-nose syndrome is caused by a cotton-like fungus that grows on noses and wings and wakes them from hibernation. Research Wildlife Biologist Sybill Amelon said bats burn 30 days worth of winter fat stored every time they break hibernation, eventually causing starvation. The disease resulted in cave closures during 2010 in an effort to prevent humans from spreading the fungus, but the effort failed. The syndrome has since reached beyond the state's borders, and caves reopened last summer.

Amelon said the effort has moved to treating infected bats with vaporized chemicals rather than trying to contain the fungus. "We've been treating the animals, rather than the substrate. It seems to be (our best chance) to reduce the rate of mortality. Where you would see 90 percent mortality, we are seeing 40-50 percent mortality."

Although it is important for cavers to give bats their space, there are plenty of passages to go around during the summer, when many bats begin sleeping outside. Missouri Fish and Wildlife Natural Resource Manager Ken McCarty said 197 caves are known just within the state park system, and most are available to the public.

"We have a variety of the caves in the park system," he said. "Access into those is managed by cave policy, and the kind of access that we allow is based on public safety. Some of these are unstable, others have very sensitive culture resources, or they have very sensitive natural resources or very fragile cave formations."

Caves can be separated into three categories:

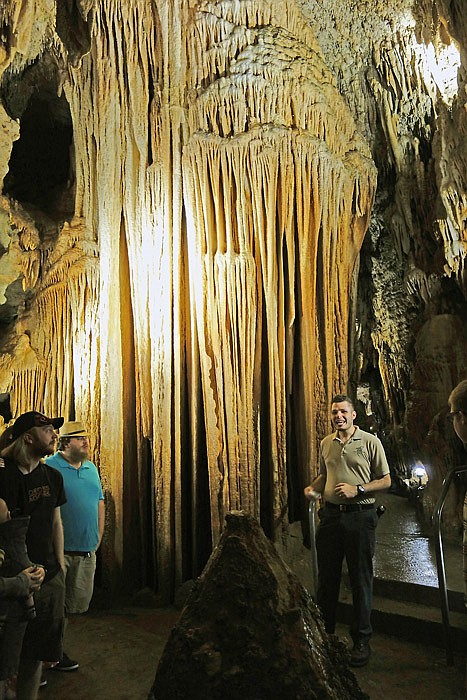

Controlled tours are given in what are known as show caves - public or private caves modified to allow people of all ages to traverse the caverns and tunnels. Some include stairs, lights and guard rails.

In wild caves, spelunkers need proper equipment and safety measures as they explore caves in their natural form with cramped quarters, dark spaces and all.

Research caves are not intended for public exploration. Due to the fragility of some cave life and historical evidence, often only scientists and other researchers are allowed inside to learn about a cave and the life within.

Each category serves a purpose intended to promote the longevity of Missouri's caving systems, from show caves that introduce youth to these underground wonders to the research caves where adults discover what caves still have to offer science.

Show caves

Private and public show caves - any cave or cavern modified for exhibition - are some of the earliest tourist attractions in Missouri. Six were open in the state before 1900. Among the modern attractions, Bridal Cave is the third most naturally ornamented cave in the United States. It is a private attraction, overlooking the Niangua Arm of the Lake of the Ozarks, available for group tours and events since 1948.

The cave is named for the Bridal Chapel chamber in which, as legend has it, is where Native Americans once held marriage ceremonies in front of a large stalactite formation that looks like limestone organ pipes. These bridal parties once had to crawl through a small hole to access the chapel. Now, dynamite blasting, removal of five metric tons of rock, 1,800 light bulbs and five miles of electric line make it possible for thousands of tours and 60-80 weddings each year.

"I think the value in (show) caves is showing the public what caves have to offer," Bridal Cave guide Joel Jones said. "I've met thousands of people in my tenure who have no idea that caves sit right underneath their feet. They are able to come in and learn in a fun way about sciences like biology, speleology (the study of caves) and geology."

Ticket supervisor Tiffany Walker said show caves teach people why it's important to preserve cave systems. "Show caves help get more people into them in a safe environment, so no matter the (person's) physical capability or age, they can go in. And once you show someone that beauty inside the cave, then it teaches them why they want to preserve it."

Guides like Jones have the dual task of education and protection. Oils from human skin repel the moisture that create formations, leaving a bruise-like space on the walls. In the past, the ends of stalactites and stalagmites have been broken off for souvenirs. Electric lights can promote unwanted algae growth. But, Jones said these are necessary risks to inspire interest in caving.

"Certain caves like this one are very deserving to be shown to the public," Jones said. "Because it's so beautiful, I wouldn't want to keep this one under lock and key."

Wild caves

Wild caves - caves in their natural condition - are the dimly lit playgrounds of underworld explorers.

"It's as if you are being Lewis and Clark seeing something for the first time," said Bryan Wilcox, a Missouri Department of Natural Resources Interpretive Resource Specialist III. "Wild caving is an exhilarating experience, because it's dark and you don't know what to expect around the corner."

Wilcox said it's also an exhilarating experience when taking the proper precautions. Well prepared cavers will have multiple light sources, hard hats, coveralls, protective pads, extra food and a group of at least four-10 people.

"With anything that is a high adventure like repelling, rock climbing or caving, you have to have the basic common sense knowledge about that recreation and what you need to have to make it safe and make it fun," Wilcox said. "You have the freedom on your own with your friends, not with a guide you don't know, but you still have to understand that the cave is a very fragile environment. It may have salamanders sleeping or bats in the cave. You could have cave deposits that are very delicate. You have to be very skillful moving through a cave, respecting those places and still having fun."

Exploring wild caves is a step up from the show caves. Wilcox said show caves are an important introductory step, where people can comfortably learn about the environment. "After you do a few of those (tours) at different caves, then the objective is, let's try one on our own and see if we can find these same kind of features, and it becomes a sort of learning experience all the time."

For those who are interested in wild caving, Wilcox recommended finding caves sponsored by the Missouri Caving Association. "Those are owners looking to support the caving experience and cave knowledge," he said. "Each cave is different with its own signature feature that they like to talk about, and that's always a good starting point."

It is important to learn the proper caving techniques before diving in. Information and programming is available at state parks like Meramec and Ozark caverns.

Research caves

In certain caves, there are more important things than fun and adventure - discovery. Riverbluff is one such cave, located on the outskirts of Spingfield. It is the oldest in North America, formed more than a million years ago. The sealed cave was accidentally discovered by crewmen blasting away rock for highway construction Sept. 11, 2001, the day of the Twin Tower attacks.

The fossils of sea creatures like blastoids and crynoids were found in the ceiling. Remains of extinct mammals like flat-headed peccary pigs, gigantic short-faced bears and mammoths along with American lions and horses were buried in silt. There they have rested since the cave was sealed, possibly by a landslide 70,000-80,000 years ago.

"We haven't found the (bedrock of the cave) yet," Missouri Institute of Natural Science board member Robert Lawrie said. "In the 15 years we've been digging, we are about 300 feet into the cave. We've got this block of silt that's been there for at least hundreds of thousands of years. That water flow has eroded and created a doorway through the entire cave. It's muddy and it's wet, but there's one little channel that water drains through until it drops into a little hole and disappears. With that in mind, we are able to explore the entire cave."

Lawrie said they have already found some worthwhile new information in the cave. Volcanic ash from Yellowstone was found with mammoth fossils, evidence the effects of its last massive eruption made it all the way to Springfield. Lawrie said the mammoths may have been using the cave for shelter as ash rained outside. It is also the first to offer evidence peccary pigs lived within caves in family units, where they could have been hunted by short-faced bears that slept in the back of the passages.

"The short-faced bear makes grizzly bears look (little)," Lawrie said. "We have scratch marks in the clay like they were done yesterday. They are 14.5 feet above the floor. This bear is enormous, and when he went extinct about 10,000 years ago, he left no DNA linkage to any modern day bear."

The Missouri Institute of Natural Science hopes to find a complete short-faced bear or giant sloth skeleton hidden in the silt, if they can obtain the funding for further research. Lawrie compared the slow process of removing silt in buckets to digging with tablespoons, so it will take time before it will be safe to open the cave for public exploration.

"There is so much to be found in there yet that to open it up to people before we even know what's in the cave, it's hard to imagine," Lawrie said. "We are still dating. We are at a million and one (years old), and we haven't even found the bed yet, so it's going to get even older. If you have a room full of silt like this, what's in it?"

Like many cave research organizations, Missouri Institute of Natural Science relies on donations to fund their Riverbluff research, but there isn't enough money to begin a major project. Its members hope people who have been fascinated by cave science - maybe after taking a show tour or going on a wild cave adventure - will help donate what they need to continue learning about the natural history and science beneath our feet in Missouri.

"I had some people in here from Pennsylvania the other day, and they were aghast that we didn't have any funding," Lawrie said. "It's probably one of the best real fossil collections in the Midwest, and we don't charge admission."