Early interventions in mental health crises or substance abuse disorders can improve public safety down the line, said Cole County Circuit Judge Cotton Walker.

About three years ago, the Missouri Supreme Court told circuit judges to assess what can be done to prevent people from repetitively appearing in courtrooms, as part of a broad justice reinvestment initiative.

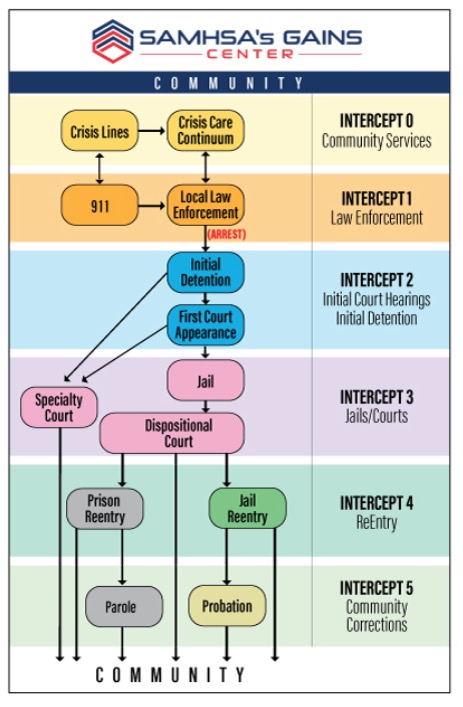

The court is now pushing for statewide implementation of a Sequential Intercept Model (SIM), which details how individuals with mental health and substance use disorders come into contact with and move through the criminal justice system, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) website.

Identifying need

Mental health professionals had pinpointed a number of resources to bring to bear early on when trying to intervene in behavioral health crises or substance use disorders. And as they went through the resources available in and around Cole County, stakeholders realized they had many of the resources they needed for interventions occurring as people advanced along a public safety continuum.

About two weeks ago, Walker said, a man on probation who is in a treatment court, had engaged with the treatment court briefly, but "disengaged" and ended up back in custody on a warrant. Walker, who presides over treatment courts, had issued the warrant.

"He has not gone to prison, but he came out of jail on a criminal felony plea to treatment court," Walker said.

Walker later ordered him released so on the next day he could report back to treatment court and court staff could engage him again.

"He has very little -- what we call -- recovery capital. He doesn't have great family support. He doesn't have money. He hasn't had a job in a while. He doesn't have a place to live regularly," Walker said. "He's a little more resourceful than somebody who lives on the street. He's more of a couch-hopper and has been for years."

The court tried to arrange timing with the jail so the man could return to treatment court in time the next day. But circuit court staff did not realize he had a city warrant.

Walker ordered him released Tuesday after he'd been in jail for several days. But, Jefferson City Court has its court Wednesday. The man remained in jail on a city warrant.

Walker called the county and learned the man remained in jail too late to attend treatment court.

"I said, 'OK, let him know that when he's released, the team is expecting him to check in. The first thing he needs to do is go to the crisis access point,'" Walker said. "Otherwise, we would have had nowhere for him to report after 5 o'clock."

Crisis access points (formerly known as crisis stabilization centers) are 11 sites situated around the state, including one in Jefferson City, where folks experiencing behavioral health crises may go for up to 23 hour to receive resources. Law enforcement officers may also deliver people who are in crisis whom they've come in contact with to the sites. Gov. Mike Parson (and the Legislature) included $15 million in the 2021-22 budget to establish six new sites and support the then-existing five.

The community behavioral health liaison who runs the access point called Walker the next morning to let him know the man showed up. The liaison said staff at the access point assessed him and found he was not in crisis. Staff provided him with several resources and scheduled followup services 30 days later.

"Wow, what a great opportunity. It happened to be treatment court, but it could have been somebody in pretrial," Walker said.

Walker said the Cole County Circuit Court provided a report to the Supreme Court after its early 2020 request for assessments. The local courts provided a report to the state in mid-2021. And in community meetings held after the request, stakeholders went through a SIM mapping process -- and focused on identifying gaps in services in each of the sequences in the local SIM.

Looking at a SIM

Mark Munetz, Patricia A. Griffin and Henry J. Steadman developed the SIM in the early 2000s to help communities address the disproportionate number of people with behavioral health concerns entering the criminal justice system.

The SIM helps communities identify resource and gaps in services at each intercept and develop local strategic action plans.

Everybody who enters the SIM has one thing in common -- they all eventually return to their communities.

"If we don't have resources for somebody who comes into the criminal justice system, or when they are done with the criminal justice system, they are going to be offending again," Walker said. "The point is that if we're not getting to them early and getting them treatment here, then we're not helping public safety."

He said courts are trying to readjust the idea that simply putting people in prison doesn't rehabilitate them.

"They're going to come back to the community, and we haven't changed a thing," Walker said. "It has not worked. That's where the Supreme Court came from."

The SIM mapping process brings together leaders and different agencies and systems to work together to identify strategies to divert people with mental health concerns or substance use disorders from the justice system into treatment.

The Cole County Circuit Court hosted a SIM mapping workshop in September.

SIM mapping workshops help stakeholders determine what resources are available for people, depending on where they are in the court system. The workshops then determine what resources are lacking for each step along the way.

By collaborating in the workshops, stakeholders identify local behavioral health services that can support diversion from the justice system.

The workshops can teach community leaders what diverts people from the system and what emerging practices show promise. The workshops create customized, local maps and action plans to address identified gaps.

The first intercept, known as "Intercept 0," is community services. The intercept involves opportunities to divert people into local crisis care services. Resources are available without requiring people in crisis to call 988 or 911, but sometimes 911 and law enforcement are the only resources available.

The intercept connects people with treatment or services, and diverts them from arrest or criminal charges. An example would be connecting this person to the crisis access point, like Walker's client. However, that man, because he was already in the judicial system, and was being reintroduced into the community, fell into the "Intercept 4" level of support.

"Intercept 1" is law enforcement. This intercept involves diversion performed by law enforcement and other emergency service providers who respond to people with mental and substance use disorders. It allows people to be diverted to treatment instead of being arrested or booked into jail, according to the SAMHSA website.

In this case, the law enforcement officer might connect the person with a community liason, a mental health professional who connects folks eperiencing behavioral health crises with some of the resources they may need, such as an access point.

"Intercept 2" occurs during initial court hearings or initial detentions. The intercept involves diversion to community-based treatment by jail clinicians, social workers or court officials during jail intake, booking or initial hearings. The court might connect the defendant with treatment court or with a provider, such as Compass Health.

"Intercept 3" is within the courts and jails. It involves diversion to community-based services through jail or court processes and programs after a person has been booked into jail. It includes services that prevent the worsening of a person's illness during their stay in jail or prison.

In these cases, the defendant could be connected with programs within the jail. They might see a mental health professional within the jail. Walker said he and Cole County Sheriff John Wheeler have discussed the possibility of creating a "recovery pod" in the jail, but discussions are at a very early stage.

"Intercept 4" occurs during re-entry into the community. It involves supported re-entry after jail or prison to reduce further justice involvement of people with mental and substance use disorders. It involves re-entry coordinators, peer support staff or community partners to link people with proper mental health and substance use treatment services.

"Intercept 5" is community corrections. The intercept involves community-based criminal justice supervision with added supports for people with mental and substance use disorders to prevent violations or offenses that may result in other jail or prison stays, SAMHSA states. That would involved having programs in prisons before people are released, but having programs available when the return to communities.

Connecting with resources

Ted Solomon, a local community behavioral health liaison, said people in his position typically already know what resources are available for clients. The liaisons are responsible for coordinating services for people with behavioral health needs who have come to the attention of the criminal justice system.

Even for liaisons, a September SIM community mapping meeting was helpful.

"Just to be reminded of resources is not a bad thing," Solomon said. "I think the big help will be continued follow-up."

Going back to 2021, stakeholders have participated in "gaps in opportunities" exercises, Walker said.

Having already identified gaps, Cole County led much of the state in progress toward implementing the SIM, Solomon said. The county was only the third to host SIM mapping sessions among stakeholders. And in a September meeting (this year) began to focus on priorities.

It created work-groups for some of the county's biggest gaps.

"Some meetings will be scheduled to continue working on that stuff," Solomon said.

Priorities that came out of the September meeting included tackling housing and transportation issues, creating a resource clearing house, polishing early intervention strategies, improving juvenile education and others, Walker said.

There were discussions about whether the community should conduct a SIM workshop only for juvenile education, he said. One of the issues that came up in September was the use of peers to assist folks with behavioral health or substance use issues.

"We are using (peers) in treatment court," Walker said. "The discussion (at the September gathering) was how to use them before (people) get to treatment court? How to use them with community partners?"

A goal is to intercept behavioral health or substance use issues before people end up with a felony charge, he said.

"I feel like I've got an obligation to the community to continue the effort to connect people before they get to a felony," Walker said. "It seems senseless to just sit up here and wait -- 'Oh, now she's got a felony. Now, we'll help you.' That's not community safety. That's not wellness."