A man of devout faith and an ardent morality, teacher Richard Baxter Foster rode with martyr John Brown in Kansas, volunteered to lead newly recruited black soldiers, opened Lincoln Institute and still had 30 years left to give to the ministry.

"They came of the very best New England stock - sturdy God-fearing people, who for many generations have been ready to stand for truth and righteousness whatever might come to themselves. And God has honored them, because they have honored him," former Howard University President Jeremiah Rankin said of Foster and his ancestors.

Before he was the first principal of Lincoln in August 1866, Foster was a lieutenant in the 62nd U.S. Colored Infantry, which came up with the school idea in January 1866 when Foster was mustered out of service.

For many months prior, Foster had written to his wife, Lucy, longing to come home to her but not yet having a clear direction of what to do next. He had worked as a teacher in Illinois and a farmer in Iowa.

"My constant question was: Have I any special work to do however humble in preparing this new time? And my constant prayer was, that if there were such work Providence would point it out and show me how to do it," Foster said in a speech in June 1871.

His fellow officers concocted the idea of a school open to blacks in Missouri as an extension of the education they had provided their soldiers in the 62nd. Between officers and enlisted of the 62nd and fellow Missourians in the 65th U.S. Colored Infantry, Foster had about $6,500 toward the venture.

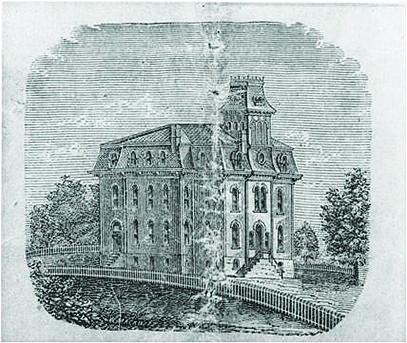

Within six years, Foster had grown the school from two pupils in an abandoned log room to erecting the institution's first building.

All the while, Foster longed to put his faith into full-time action.

When he felt the school was on sound footing, Foster moved to Kansas, became ordained in the Congregationalist denomination and preached for 30 years.

Foster was born in 1826 in Hanover, New Hampshire, where he attended Concord Literary Institution and Henniker Academy before advancing to Dartmouth, where he earned his degree in 1851.

Within the next three years, he taught school in Illinois, married and lost Jemima Ewing, saw the birth of his first son, Walter, and lost his mother, Irene.

Foster headed farther west. In Iowa, he met and married Lucy Reece in March 1855. Three boys were born in Iowa, before they moved to Nebraska. In 1856, he was involved in campaigns against border ruffians and rode with John Brown.

In September 1862 at age 36, Foster enlisted as a private in the 1st Nebraska Volunteers, an infantry turned cavalry, where he was promoted to corporal. He was at the Battle of Cape Girardeau April 26, 1863.

Another son was born in Nebraska before Foster was commissioned a second lieutenant with the 62nd U.S. Colored Infantry Dec. 29, 1863, at Benton Barracks in St. Louis. He served the regiment as acting adjutant for much of the time, while also leading Company I.

In June 1865, he was brevetted captain for gallantry and meritorious service at the Battle of Palmetto Ranch. George Chase said in the May 10, 1888, National Tribune that Foster, who was in command of the rear guard, gave the last command to fire in the last battle of the war.

Before he mustered out of service in January 1866, another son was born in Iowa. By the time he and Lucy moved to Jefferson City, they had five boys of their own.

During the six years Foster was in Jefferson City, building Lincoln Institute, they had three more boys and twin girls. To make ends meet, he taught school in the community and also wrote for the Missouri State Times.

And he began his studies for the ministry, being licensed to preach by the Methodist Quarterly Conference in 1868.

"Father thought Jefferson City would be a good place in which to start his school. That the people of Jefferson City did not agree with him made no difference whatsoever," his daughter Grace Brown wrote in "Lifelines." "They could not rent a building, not even a church. Everyone was opposed to having a school for Negroes in their midst; the crazy Yankee could take his school somewhere else, or go jump in the river.

"There was no room at the inn and the school was born in a manger."

The Foster family faced many trials from the community. When they tried to force them out, Foster posted a notice he would protect his home, Brown wrote.

"They were humiliated and harassed at every turn. Mother had no friends. The children were stoned and not allowed to attend the public schools. Father taught his sons. The oldest boy, Festus, helped teach the Negroes when but 13 years of age."

The Foster family of 13 moved to Osborne, Kansas, where he served the 10 years as pastor after being ordained Aug. 4, 1872, at the First Congregational Church. There, their last child was born in 1874. And a year later, they lost two little ones to diptheria.

"He came to Kansas when it was young and he had a part in forming her history and high ideals - upheld the principle of justice to all races and advocated prohibition, when it was even less popular that it is now," Brown wrote in 1926 in "A Tribute of Love." "We had only the bare necessities of life. There were more mouths than meat and children than chairs, but we always had books."

Foster served eight more congregations in Kansas, before moving to Oklahoma in 1890.

At the opening of the new territory, Foster delivered the first sermon preached in the state, Brown said.

"He was always very proud of this distinction."

In Stillwater, Oklahoma, he organized the First Congregational Church. There, he preached four years while also earning his doctorate of divinity from Howard University in 1891, serving as the first superintendent of schools, and publishing "What is Congregationalism?"

He preached two years in Perkins, Oklahoma, before settling into his last parish in Okarche, Oklahoma, where he became an instructor at Kingfisher College's theological department. He published "What do Congregationalists Believe?" in 1896.

Foster died March 30, 1901, at age 74.

"Nobleness and greatness of heart are imperishable virtues. Christian love and sacrifice write indelibly upon hearts in all generations. Into my life came a man who had all these characteristics," Brown recorded from one of her father's former church members, turned pastor.

"A man of broad sympathies, of deep consecration, one of our deepest thinkers, and above all one who walked life's pathway with the Man of Galilee ... humorous, kind, gentle, strong, prayerful and active."