ST. LOUIS (AP) - Descendants of a man who vanished after winning a historic legal fight to become the first black student at the University of Missouri's law school had hoped an FBI cold-case initiative focusing on possible racially motivated deaths from the civil rights era would unearth clues about his disappearance.

But federal records obtained by The Associated Press and subsequent interviews show that Lloyd Gaines' disappearance in 1939 was not among the more than 110 cases reviewed between 2006 and at least 2013 under a Department of Justice initiative and the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act.

It's a pattern familiar to Gaines' family - the FBI twice declined requests in 1940 and 1970 to help find Gaines, who was 28 and last seen leaving a Chicago boardinghouse. Theories about his disappearance range from foul play at the hands of the Ku Klux Klan to a self-imposed exile in Mexico.

"They should have done more way back when," said nephew George Gaines, a retiree who lives in San Diego. "I don't believe there would have been much uncovered more recently. People die, memories fade, records are destroyed. And some people choose not to remember."

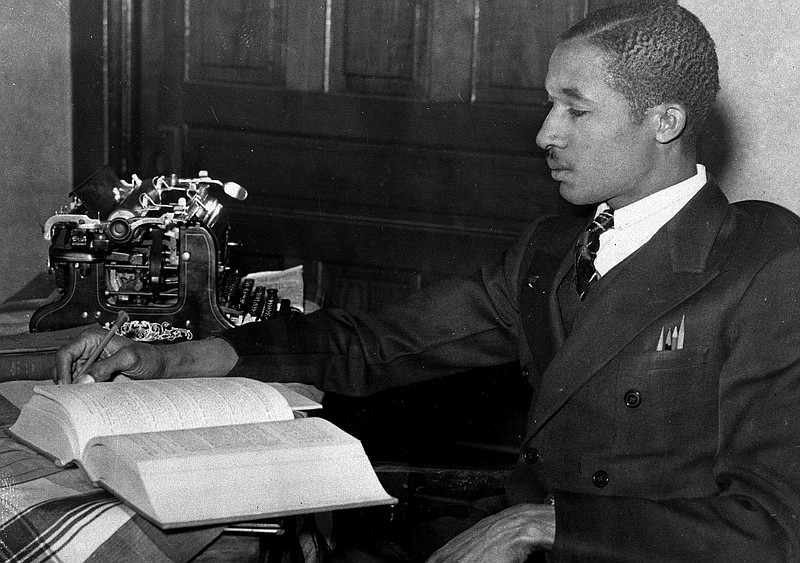

Gaines, a Mississippi native who grew up in St. Louis, was an honors graduate of historically black Lincoln University in Jefferson City, Missouri. He sued the state's flagship university after being denied admittance to its law school because he was black. His case went to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in 1938 that Missouri must either admit Gaines or establish a separate law school for blacks.

Previously, any black person in Missouri who wanted to attend graduate school was sent to neighboring states that accepted minorities, at Missouri's expense.

The university chose to open a separate school - a bare-bones alternative in a former St. Louis beauty academy- prompting Gaines to decide to attend graduate school at the University of Michigan, where he earned a master's degree in economics. When he disappeared, his lawyers were forced to drop the case.

"It's a mystery," George Gaines said. "I do not believe he had gone that far (in the legal process) just to leave."

A now-retired FBI spokesman said in 2007 that Gaines' case was being considered for review, but an FBI official in Washington said recently that such an inquiry would have been outside the scope of the cold-case effort.

"Most of the deaths reviewed as part of the FBI's Civil Rights Cold Case Initiative occurred in the 1960s, and in most of those cases no prosecution was possible because subjects and witnesses are deceased," FBI spokesman Christopher Allen said. "Lloyd Gaines' disappearance, though mysterious, could not be determined to be a homicide, and considering the disappearance occurred nearly 70 years prior to the passage of the Act, chances were remote that any witnesses or subjects could be found, or new investigative leads developed."

The handful of cases that went to trial under the FBI effort include a 2010 state prosecution of former Alabama state trooper James Fowler, who pleaded guilty to manslaughter in the 1965 shooting death of Jimmie Lee Jackson following a protest march and was sentenced to six months in jail.

Gaines received an honorary law degree from Missouri in 2006 and a posthumous law license that year from the state bar association.