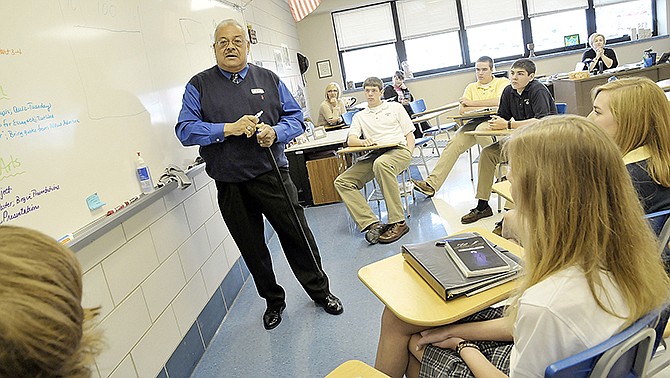

The first African-American to graduate from Helias Catholic High School recently shared memories of growing up in Jefferson City with a class of sociology students who attend his alma mater.

Although segregation was a part of everyday life for black families during that era, Sidney Reedy - who attended between 1956 and 1960 - typically did not encounter racist attitudes at Helias.

"I was treated very well here," he said Thursday. "I love this place."

One of his most-memorable high school experiences happened when the Helias band and the football team traveled to Centralia for a game. Centralia fans - furious over their team's loss - attempted to slash the bus's tires. Hustled away from the school, Helias's leaders wanted to stop at a country diner after the game. Reedy declined to come inside.

"I'm not hungry," he told them, because he knew the restaurant wouldn't serve him. He was right, and Helias's leaders made a decision to find another place to eat.

"I hated to be the butt of it, but it was a real lesson for my fellow band members," Reedy said.

Reedy's race did prevent him from attending his junior and senior proms - which hurt. As a class officer, he was tasked with decorating for the dance. The school had a rule: Only Catholics could attend.

"There were no black Catholic girls my age," he explained. "My mom said I was a fool for helping, but I felt it was my duty. I remember looking at the decorations ... it was sad."

If life in Jefferson City was relatively calm, civic life elsewhere in the nation was extremely tumultuous.

In 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court declared that separate public schools for black and white students were unconstitutional. In 1957, President Dwight D. Eisenhower ordered the Army's 101st Airborne Division to escort nine African-American students past angry mobs so they could attend Little Rock's Central High School.

Although not as widely enforced as in the Deep South, segregation was nevertheless supported and practiced in Mid-Missouri when Reedy, now 71, was a teen. Part of his mission Thursday was to shed light on history that today's teens have difficulty fathoming.

Reedy's family - his parents were teachers at Lincoln University - was one of the few to straddle Jefferson City's African-American and Catholic worlds.

Reedy - whose family tree is marked by a mix of races - has two connections to Catholicism. Not only does his family tree include Irish immigrants who settled in America, his father and uncle also lived with a white Catholic family while enrolled as Lincoln University students. In exchange for helping with the family's chores, the brothers boarded with the Edwards family and ultimately converted to their faith and were baptized in 1923.

It wasn't typical for African-American families to attend predominantly white Catholic churches back then. It wasn't always easy, and the family found itself ostracized from both sides.

One of his most-hurtful memories happened when he was 6 years old

Blacks weren't permitted to participate in the Easter egg hunt organized by white families. Although his mother traditionally contributed three dozen eggs to the hunt organized by black mothers, his family wasn't welcome in that community, either.

"When you're 6, it means a lot," he said.

Reedy also recalls two occasions when his family would sit down in church and other congregants would move elsewhere.

Cub Scouts was an early testing ground for integration. White parents organized a meeting to talk about allowing a black child into their homes. Ultimately, he participated with great joy.

"I had three wonderful den mothers," he said.

Reedy also told the Helias students about his experiences with segregation at the city's two movie theaters and the town's swimming pools. Even the city's restaurants were segregated.

Although Landwehr's dairy allowed blacks to purchase ice cream and sit down, Central Dairy treated black customers differently. Black customers could purchase ice cream and take it to go, but they couldn't sit in the booths, Reedy recalled.

Often, the white friends he made at school failed to recognize how deeply segregation affected black residents. Once a friend asked if he wanted to attend a cartoon festival at the Capital Theater. He declined because "I knew we couldn't sit together," he said. Instead he pretended his mother wouldn't let him go.

Reedy's stories about segregation and racism shocked the Helias teens who heard them.

"I was in disbelief," said Anna Porting, 17. "That's not how I was raised."

"I didn't know it was that bad," added Mariel Schnieders, 17.

After graduating from Howard University in Washington, D.C., Reedy - a retiree who lives in University City - spent most of his career as a librarian in St. Louis.

Good memories or bad, Reedy said they all formed who he is today.

"Every experience you have is going to affect you for the rest of your life," he said.