NEW YORK (AP) - Hear David Letterman, who knows something about comedy, pay tribute to the comic artistry of Bruce McCall.

"The standard by which comedy should be judged," says Letterman.

Relaxing at his mid-Manhattan offices after a "Late Show" taping last week, he continues celebrating the man he has just played host to (not for the first time) as one of that night's guests.

He calls McCall's writing and illustrations "a perfect combination of the ridiculous and hyperbolic, but still with a glimmer of plausibility."

Then, when told that McCall says the two of them share "exactly the same sensibilities in humor," Letterman responds with a wary smile: "Anybody can carve meat. Some can carve it with a sharp knife, some can carve it with a dull knife. Mine," he pauses for maximum effect, "needs sharpening."

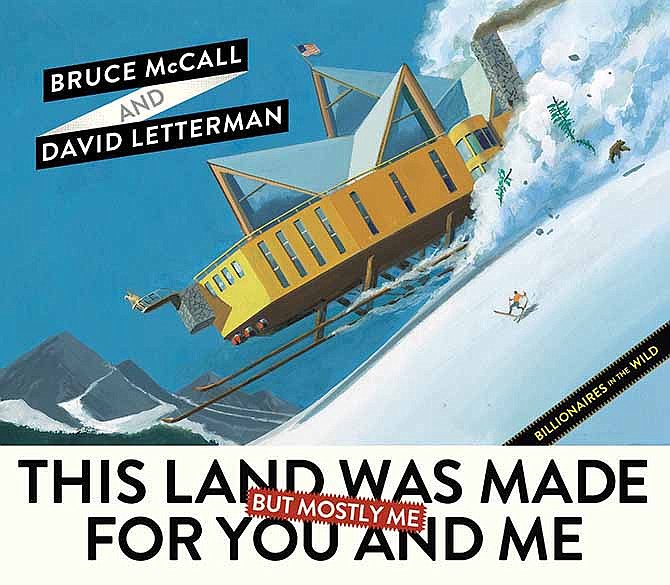

No wonder Dave teamed up with McCall for their new book, "This Land Was Made for You and Me (But Mostly Me)" with the sassy subtitle "Billionaires in the Wild" (Blue Rider Press).

Their book treats readers to the McCallian charm that Letterman has adored since the 1970s, when he stumbled onto McCall's work in National Lampoon and Esquire magazines, then became a fan of McCall's text-and-illustration classics including "Zany Afternoons" and "All Meat Looks Like South America," as well as his 50-and-counting covers for The New Yorker (the most recent last month).

McCall, now 78, depicts a wonderland of gracious living writ extravagantly large. His is a Gatsby-like world of urbane but unconscionable excess that feels fancifully authentic, that indeed might have existed in bygone times, or might today, or might tomorrow - that is, if expense, taste and even minimal respect for Mother Nature were no object.

The new book stemmed from Letterman's off-hours whiled away at his Montana ranch, where, around him, he saw fortunes and hauteur fuel outrageous back-to-nature lifestyles.

"I kept thinking, I would just like to see one Bruce McCall rendering of a million-acre ranch," Letterman recalls.

"This Land" goes even further. Broadening its scope beyond just Montana's "billionaires in the wild," it goes global with dozens of imagined case histories, like the 23-year-old casino titan who buys an island in the Fijis, where he installs a nuclear power plant to furnish hot water to his Olympic-size Jacuzzi, and a "Bangalorean packaged-suttee mogul" who removes the craggy peak of Mount Everest and transports it to the roof of his ritzy Manhattan apartment house, with his valet posted at the summit to serve martinis to parched mountain-climbing guests.

Closer to home: the fire-insurance baron's mile-long fireplace in his Wyoming manse. Or the Montana hunting lodge whose vast living room serves, for added convenience, as an indoor landing strip for his private plane.

Granted, Letterman, who at 66 is a well-heeled TV star, might be accused of guilt-by-association with McCall's "brainless rich" as he mocks high rollers who turn unspoiled nature into a private Disneyland.

But when he discovered Montana more than 15 years ago and found it "stunning," he resolved to dodge the southwestern part of the state "where you have all your famous people. I said, 'I'm not gonna move out there if it's gonna turn into the Hamptons.'"

Instead, he staked his claim (he declines to specify the acreage) in the state's northern realm some 100 miles from the Canadian border, shunning amenities such as a swimming pool, hot tub, tennis court or indoor rifle range, he says.

"We have some buffalo, some horses, a lot of barbed wire and a lot of weeds. And wind!"

Also in his defense: Letterman became one of the McCall Cognoscenti back when he was still entrenched in the 99 percent, only subsequently soaring into 1 percent prosperity "because of good, dumb luck," he insists.

Letterman sounds his hearty, cadenced chuckle at the thought that his time in Montana has been spent undercover, collecting intel on those lavish interlopers.

"I couldn't have called them on it if I wasn't there to begin with," he reasons with a laugh. "You got to be there to see it!"

Having been seen, the path to a book that would skewer it was blazed by McCall's daughter, Amanda, a writer who happened to work at "Late Show."

"I would yack to her about what I was seeing in Montana," Letterman says. "I don't know if she knew I was campaigning for her dad to do this project, but she knew I loved his work."

She took the hint and became the vital go-between.

As her father reports with customary bluntness, "One day she said to me, 'Dave has a ranch in Montana and he's sick of seeing all these nouveau riche egomaniacs build huge mansions and reroute rivers and cut down forests and otherwise blight the landscape, and he wanted to make fun of it. He thinks you'd be the right guy to visualize it.'"

McCall, a fireplug of a chap with a wispy beard and a deadpan manner, is holding forth in the comfortable Upper West Side apartment he shares with his wife, Polly, a psychotherapist, where his creations issue from a studio he wryly describes as "an extra bedroom - hardly an atelier."

Letterman, he makes clear, "admires my work way too much. I never went to art school, never had a lesson. I don't know anything about art."

Today a self-described Canadian expat, McCall grew up in southern Ontario as one of six siblings with "a horribly unhappy home life. My mother was an alcoholic, my father was a tyrant. We were poor. We had no space, we had no joy. I escaped by drawing pictures and writing stupid stuff to entertain myself."

His all-important lodestar: a cache of back issues of The New Yorker, to which his parents subscribed.

"I found them one day when I was 11 years old in the closet, lovingly bound," he recalls. "So sophisticated, funny and sharp! It made me aspire to live in that world."

A career in commercial art and advertising (which he hated) eventually brought him to New York (which he loved), where he began freelancing on the side. Twenty years ago he took the plunge to full-time illustrating and writing, landing many assignments, including a plum contract from - where else? - The New Yorker.

"But I work alone," he notes. "I don't collaborate with anybody. So originally I thought, 'How's this book gonna work?'"

Really well. "It was a field day for me to come up with ideas that were visually striking that I could tie to an environmental disaster of one kind or another."

Even so, the back-and-forth collaboration took several years.

McCall would dispatch his daughter with a new round of material, "and then," says Letterman, "we would make changes and suggestions and add or take out a line, and send it back to him. It started simply with a few sketches, and pretty soon there was a giant portfolio. And now here we go: the thing is published!"

Now that "This Land" is out, will its satire strike a blow for saving the planet? Will it raise the public's consciousness about the writer-illustrator Letterman calls "revelatory"?

Any of that would be nice, Dave allows. But it was never his main goal.

"The idea of this book was just to get more Bruce McCall drawings created," he says. "So I succeeded there."

EDITOR'S NOTE - Frazier Moore is a national television columnist for The Associated Press. He can be reached at [email protected]