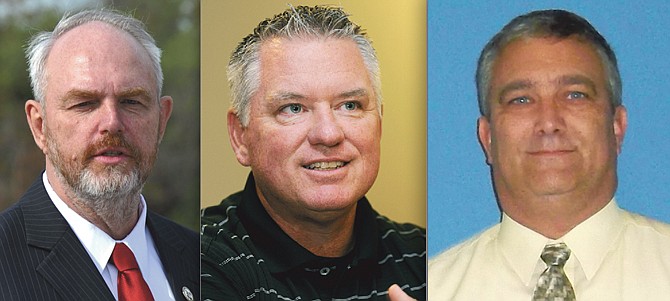

On Tuesday, Jefferson City school board incumbents Doug Whitehead and Dennis Nickelson - both key supporters of the district's plan to build a new high school to replace the existing one - face a challenge from Harold Coots, a political newcomer who would rather see the community build a second high school.

The two candidates who win the most votes Tuesday will be sworn into office in April.

Coots favors building a second high school and keeping the existing one open, to avoid concentrating so many students in one location.

He said he will be voting Tuesday against the bond issue, which if approved by voters will increase local taxes by 30 cents, thus providing $79 million for construction of a new high school and elementary school.

In the same election, voters also will be asked to raise the district's operating levy by 25 cents for transportation, security and technology. If both issues pass, property owners would pay an additional 55 cents per $100 of assessed valuation.

Coots said two schools would offer the community's teens more chances at success because more students would have a shot at participating in extracurricular activities.

"When I was in high school 35 years ago, we needed two high schools then," he said.

Whitehead and Nickelson favor building a replacement high school, an option they believe will allow the district to offer a high-quality education at the most affordable cost.

Nickelson said: "A single high school provides the lowest-cost option to give our students an excellent education. Two high schools are more expensive to operate. The school board has designed an excellent plan to meet our pressing space demands at the lowest cost."

Whitehead is concerned some advocates in the community, in their quest to find the perfect solution, are rejecting or overlooking a good plan.

"I know it's a good plan," he said. "If two high schools were the best proposal, we'd be offering it. Being a leader is taking the data, working with people and telling your story."

He added: "We certainly don't want to be here four years down the road and having to deal with dilapidated infrastructure and buying trailers."

Whitehead said that federal, state and even city revenues have deteriorated in recent years. He thinks, if funding is going to be found for schools, it's going to be local. "We need a community solution," he said.

As envisioned, the district's proposal for a new high school calls for a large new campus east of Highway 179 and north of Mission Drive. The new campus would have seven "academies," each devoted to a different set of professions, such as the health sciences or performing arts. Multiple new buildings would dot the site.

Officials with the school have said the large project could be broken into pieces so multiple local contractors have an opportunity to build the school.

Coots said that strikes him as impractical. He wonders if seven different academies could end up having seven different heating systems. From a facilities management point of view, Coots said the scenario could be a "nightmare."

Coots said the community doesn't have seven different contractors capable of installing the same heating-and-cooling system. "You've eliminated half of your contractors because they are not authorized to install" a Lennox or Carrier system, for example, he said.

Instead of seven academies sheltered in one location, Coots would prefer to see three or four academies organized at the new campus, while the old campus functions as a traditional high school.

Coots said the academies approach directs too many students toward a college-bound course of study. "Not everybody goes to college," he said.

And he worries the system demands students make choices about their future too early in life. "A college student changes their major three or four times. Now we're asking an eighth-grader to make that decision," he said.

Nickelson believes opening seven academies will break the high school into seven smaller learning communities, which will foster genuine relationships among teachers and students. "Students who feel they belong and have a purpose are more successful in school. Research indicates that there should be less than 900 in a school and that small learning communities are equal to a small school," he wrote.

He also sees academies as a way to improve the district's dropout and graduation rates. "It's a personal tragedy for students who don't earn a degree, but it's also a society tragedy," he said.

Nickelson said listeners are more amenable to the board's plan once they hear the details.

"I get fairly positive feedback," he reported. "It's a matter of understanding. But it does take time for people to understand, and that's our biggest challenge."

Doug Whitehead

Whitehead, a lifelong resident of Jefferson City, graduated from Jefferson City High School in 1983 and earned a degree from Kansas State University's Professional School of Architecture in 1988. Today, he works as director of operations for the National Biodiesel Board.

He is proud of the current Board of Education's decisions to roll back taxes for the past four years.

During his tenure on the board, school leaders "have tried to provide more with less" in order to establish a healthy reserve fund. He noted when he first arrived, the district had only 5 percent of its operating revenues in reserve. Today, those reserves have been built to about 26 percent.

Whitehead said having a healthy reserve allowed the district to purchase land for a new elementary school and high school without having to go to the taxpayers.

"It means we can recruit and retain the best teachers, because we've given a raise every year," he said. "When voters are deciding, I hope they will consider the track record."

He sees his years of experience serving the school district is an asset. "After 12 years of serving, you have a body of work experience that you can apply to future decision making. I've learned so much, and I'm not ready to quit. I love it. If I didn't love it, I wouldn't do it. I hope I get another chance to continue to serve."

His wife, Alana Whitehead, is a sixth-grade math teacher. The couple has two children: Meg, a JCHS graduate, and Ross, a 10th-grader.

Whitehead serves as vice president of the Missouri School Boards Association; he's in line to be president in June 2014.

Harold Coots

Coots, a lifelong resident of Cole County, graduated from Jefferson City High School in 1978 and Central Missouri State University in 1982 with a bachelor's of science in drafting technology. Today, he works as a project manager/architect for the Missouri Office of Administration's Division of Facilities Management, Design and Construction.

Coots said the high school inexplicably experienced a high rate of teacher turnover in recent years. "There was a big exodus recently, and we never heard why," he said.

He also is concerned that discipline at the high school has grown too lax, and he doesn't like the district's policy on fighting.

"I have talked with former and current teachers. They are concerned about the high school administration's approach to discipline. They say they send a student to the principal's office and minutes later, he's right back. Not enough is done. Kids are feeling untouchable," he said.

He feels the fighting policy penalizes innocent parties. "If you are part of a fight, you are guilty, even if you are defending yourself," he said.

Although he lives on the Jefferson City side of the Moreau River, Coots has a Lohman address. He has two sons - Steven, 18, and Thomas, 15- who are enrolled at the high school.

Dennis Nickelson

Nickelson, who has lived in Jefferson City since 1977, is an assistant professor of mathematics and physics at William Woods University in Fulton. He obtained his bachelor's of science in education in chemistry and physics from Central Missouri State University, a master's in education from Lincoln University and his doctorate from the University of Missouri.

A retired public school teacher, Nickelson was the former chairman of the science department at Jefferson City High School. He was selected as the 1994 Jefferson City Public Schools Teacher of the Year and earned the Monsanto Science Teaching Award and the Missouri Academy of Science Teaching Award.

Although his field of expertise is science, he has worked to solve academic challenges for students of all ages. He said the creation of a pre-kindergarten program was "the most positive step we've taken" in his three years on the board.

During his long tenure as an educator, Nickelson has had a leadership role in advancing science education in Missouri.

In 2006, he retired from teaching to lead the Physics First program, an initiative designed to increase the number of teachers capable of teaching physics. "Physics is fundamental to the other sciences," he said. "We trained 80 practicing teachers. We did it during the summer as a residential project."

He has served as senior staff on several professional development projects, such as the lead physical science teacher for the K-6 Missouri Science and Math project, a project pioneering the use of computers in the science classroom. He has also spent five summers on the staff of the Missouri Scholars Academy, and he has served as the Central Missouri Science Olympiad director for 11 years.

He has been an adjunct professor for Lincoln University, Linn State Technical College, Columbia College and the University of Missouri.

His wife, Nancy, is a retired special services teacher for JCPS. Their children, Ben and Karen, are graduates of JCHS.